Trauma’s Impact on Mental Health: Healing & Support in US

Trauma profoundly reshapes mental health, manifesting in various conditions requiring specialized care; in the US, navigating accessible therapeutic and support systems is crucial for fostering resilience and promoting comprehensive recovery.

The human experience, while rich with joy and connection, is also inescapably vulnerable to profound distress. Among the most challenging forms of this distress is trauma, an emotional response to a terrible event that can leave lasting imprints on an individual’s psyche. Understanding the impact of trauma on mental health: finding healing and support in the US is not merely an academic exercise, but a vital exploration into how we, as a society, can better recognize, respond to, and ultimately heal from these deep wounds.

Understanding the Multifaceted Nature of Trauma

Trauma is more than just a bad memory; it’s a deeply distressing or disturbing experience that can overwhelm an individual’s ability to cope. It leaves an indelible mark on the brain, particularly in areas responsible for emotion, memory, and threat perception. The immediate aftermath can involve shock and denial, but the long-term effects often emerge as chronic mental health conditions if left unaddressed. It is crucial to recognize that trauma’s definition extends beyond a single, dramatic event, encompassing repeated exposures to distressing situations, and even vicarious trauma experienced by those close to victims.

Types of Traumatic Experiences

Traumatic experiences manifest in diverse forms, each carrying potential for significant psychological impact. Understanding these categories helps in tailoring therapeutic approaches and fostering empathy.

- Acute Trauma: This results from a single overwhelming event, such as a car accident, natural disaster, or a one-time assault. The shock is immediate and intense, often leading to acute stress disorder which can evolve into PTSD.

- Chronic Trauma: This stems from prolonged and repeated exposure to highly stressful events, like domestic abuse, ongoing neglect, or long-term combat exposure. Its insidious nature erodes an individual’s sense of safety and self over time.

- Complex Trauma: This refers to trauma that occurs repeatedly and cumulatively, often in interpersonal contexts, especially during developmental periods. Examples include childhood abuse (emotional, physical, sexual), neglect, or witnessing sustained violence. It profoundly impacts identity, relationships, and emotional regulation.

- Secondary or Vicarious Trauma: This affects individuals who are exposed to the traumatic experiences of others, such as first responders, therapists, or caregivers. They may not directly experience the event but absorb the emotional toll, leading to symptoms similar to direct trauma exposure.

These classifications are not rigid boundaries, but rather tools to help us understand the vast spectrum of experiences that can induce a traumatic response. The individual’s perception, resilience, and support system play significant roles in how a traumatic event is processed and integrated into their life narrative. Recognizing the varied forms of trauma is the first step toward effective intervention and compassionate support. Beyond these classifications, there’s also the element of collective trauma, which societies experience after major events like pandemics or large-scale social unrest, affecting the mental well-being of entire communities.

The Profound Psychological Residues of Trauma

The brain, in an attempt to protect itself during a traumatic event, often goes into overdrive, activating the “fight, flight, or freeze” response. When this acute stress response becomes maladaptive and prolonged, it can lead to a cascade of psychological challenges. The limbic system, particularly the amygdala, becomes hyperactive, while the prefrontal cortex, responsible for executive functions like rational thought and emotional regulation, can become underactive. This neurobiological shift explains many of the distressing symptoms experienced by trauma survivors.

Common psychological outcomes of trauma include:

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD):Characterized by intrusive thoughts, flashbacks, nightmares, avoidance behaviors, negative alterations in mood and cognition, and hyperarousal.

- Anxiety Disorders:Generalised anxiety, panic attacks, and social anxiety often co-occur with trauma, as the individual’s nervous system remains on high alert.

- Depression:Feelings of hopelessness, low energy, anhedonia (loss of pleasure), and suicidal ideation are common as individuals struggle to cope with the emotional burden.

- Substance Use Disorders:Many individuals turn to drugs or alcohol as a coping mechanism to self-medicate the pain, numb flashbacks, or manage overwhelming emotions.

Moreover, trauma can severely disrupt an individual’s sense of self and their ability to form healthy relationships. They may struggle with trust, intimacy, and a pervasive feeling of shame or guilt, even when they are the victim. The fragmentation of memory, emotional dysregulation, and a skewed worldview are further psychological residues that complicate daily functioning. These impacts are not signifiers of weakness, but rather powerful evidence of significant psychological injury that demands comprehensive care and understanding.

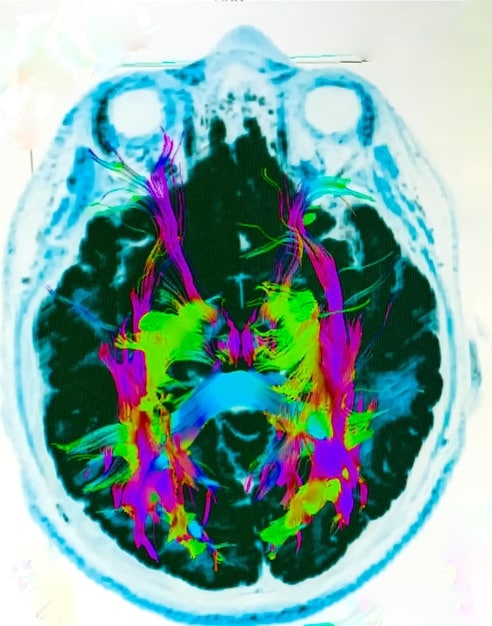

Neurobiological Changes: How Trauma Rewires the Brain

Trauma doesn’t just affect our thoughts and emotions; it leaves a tangible mark on the very structure and function of the brain. The brain’s immediate response to threat prioritizes survival, triggering changes that, while adaptive in moments of danger, can become maladaptive in the long term, impacting everything from memory to emotional regulation. This neurobiological rewiring underscores the complexity of trauma and the necessity of targeted therapeutic interventions.

The primary areas affected by trauma include:

- The Amygdala: This almond-shaped cluster of neurons is the brain’s alarm system, responsible for detecting threats and initiating fear responses. In trauma survivors, the amygdala often becomes hyperactive, leading to an exaggerated “fight, flight, or freeze” response even in safe situations.

- The Hippocampus: Crucial for memory formation and retrieval, particularly for contextualizing memories. Trauma can shrink the hippocampus, impairing its ability to put experiences into proper temporal and spatial context. This can lead to fragmented memories, difficulty distinguishing past from present, and vivid flashbacks that feel like they are happening again.

- The Prefrontal Cortex (PFC): Involved in executive functions such as decision-making, impulse control, emotional regulation, and rational thought. Trauma can reduce activity in the PFC, making it harder for individuals to regulate their emotions, think clearly under stress, or control impulsive behaviors.

- The Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex (vmPFC): A specific part of the PFC that helps suppress fear responses from the amygdala. In trauma, reduced vmPFC activity means the amygdala’s alarm signals are less likely to be dampened, contributing to persistent anxiety and hypervigilance.

This interplay between brain regions means that trauma survivors often experience a state of chronic hyperarousal, making them easily startled, irritable, and prone to emotional outbursts. Sleep disturbances are common, as the brain struggles to switch off its internal threat detection system. Furthermore, these changes can affect neuroCHEMICAL pathways, altering levels of neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and cortisol, which further contribute to mood disorders and heightened stress responses. Understanding these fundamental shifts provides a powerful basis for therapeutic approaches that aim to help the brain relearn safety and restore its natural equilibrium.

Challenges and Barriers to Healing in the US Context

While the understanding of trauma and its impact has grown significantly, the path to healing in the United States is often fraught with challenges. Navigating the complex healthcare system, overcoming societal stigmas, and accessing appropriate resources can themselves be overwhelming for individuals already struggling with the profound effects of trauma. Addressing these barriers is essential for creating a more equitable and effective system of support.

Systemic and Societal Obstacles

Several pervasive issues hinder effective trauma recovery in the US:

- Access to Care: Despite advancements in mental health awareness, disparities in access to quality care persist. Geographic limitations, lack of qualified practitioners in rural areas, and long waiting lists in urban centers mean many individuals cannot receive timely intervention.

- Financial Barriers: The cost of therapy, medication, and specialized trauma treatments can be prohibitive, even with insurance. High deductibles, limited coverage for mental health services, and out-of-network costs force many to forgo essential care.

- Stigma: Despite public awareness campaigns, a significant stigma still surrounds mental illness, particularly trauma. This can discourage individuals from seeking help, fearing judgment from family, friends, or employers. Cultural factors can also play a role, with some communities having particular hesitations about mental health treatment.

- Provider Training and Cultural Competency: Not all mental health professionals are adequately trained in trauma-informed care. Furthermore, a lack of cultural competency among providers can lead to misdiagnosis or ineffective treatment for diverse populations.

Beyond these direct barriers, the fragmented nature of the US healthcare system can complicate care coordination. Individuals may struggle to find therapists, primary care physicians, and social services that communicate effectively and provide holistic support. The legal and justice systems can also re-traumatize survivors, especially in cases of crime or abuse, due to insensitive procedures or a focus that inadvertently places blame on the victim. Acknowledging these challenges is the critical first step in advocating for systemic changes that elevate mental health care for trauma survivors.

Pathways to Healing: Therapeutic Modalities in the US

Despite the challenges, the United States offers a wealth of therapeutic modalities specifically designed to address the deep-seated effects of trauma. The landscape of trauma treatment has evolved significantly, moving beyond traditional talk therapy to incorporate approaches that work directly with the body and the nervous system, recognizing trauma’s physiological imprint. Finding the right pathway often involves a customized approach, combining various techniques tailored to individual needs and preferences.

Evidence-Based Trauma Therapies

Effective trauma treatment focuses on helping individuals process traumatic memories in a safe environment, redefine their narratives, and regulate their emotional and physiological responses. The most widely recognized and evidence-based therapies include:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): A broad approach that helps individuals identify and challenge unhelpful thought patterns and behaviors that developed in response to trauma.

- Trauma-Focused CBT (TF-CBT): Specifically adapted for children and adolescents, involving both the child and caregiver in the therapeutic process, focusing on psychoeducation, relaxation, cognitive processing, and exposure techniques.

- Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT): A specific type of CBT that helps individuals understand how trauma changes their thoughts and beliefs, and challenges distorted thinking patterns related to the traumatic event.

- Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR): This therapy involves recalling distressing memories while simultaneously receiving bilateral sensory input (e.g., eye movements, tones, or taps). It helps to “reprocess” traumatic memories, reducing their emotional charge and integrating them more adaptively into memory networks.

- Somatic Experiencing (SE): Developed by Peter Levine, SE focuses on the physiological responses to trauma. It helps individuals release “stuck” traumatic energy in the body by developing increased awareness of bodily sensations, leading to a more regulated nervous system.

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT): While originally developed for Borderline Personality Disorder, DBT is highly effective for trauma survivors, especially those struggling with emotional dysregulation, self-harm, and chronic suicidal ideation. It teaches skills in mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotion regulation, and interpersonal effectiveness.

Beyond these, other valuable approaches include Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, which integrates body-oriented and verbal techniques; art therapy, which provides a non-verbal outlet for expression; and various forms of group therapy, offering peer support and shared experience. The integration of medication, when appropriate, can also play a vital role in managing severe symptoms like anxiety, depression, or sleep disturbances, providing a stable foundation for therapeutic work. Healing from trauma is a journey, not a destination, and it often involves a flexible, multifaceted approach.

The Crucial Role of Support Systems and Community in Recovery

While individual therapy is pivotal, healing from trauma is significantly bolstered by robust support systems. No person is an island, and the journey of recovery can be lonely without understanding and connection. In the US, a diverse array of community-based resources, support groups, and trained professionals complement formal therapy, providing a holistic network for survivors to reclaim their lives. These networks foster resilience, reduce isolation, and offer practical assistance that therapists cannot always provide.

Building a Foundation of Connection and Care

Effective support systems encompass multiple layers, ranging from intimate relationships to wider community resources:

- Family and Friends: Educating loved ones about trauma and its effects can transform their support from well-meaning but potentially harmful advice (“just get over it”) into informed empathy. Open communication, patience, and non-judgmental listening are invaluable.

- Peer Support Groups: Organizations like RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network), NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness), and various local community centers offer trauma-specific support groups. Here, survivors can connect with others who have similar experiences, reducing feelings of isolation and shame, and sharing coping strategies. The shared experience normalizes their feelings and demonstrates that healing is possible.

- Community Resources: Beyond formal groups, many communities offer resources such as crisis hotlines, domestic violence shelters, veteran support services, and legal aid. These provide immediate safety, practical assistance, and pathways to further specialized care.

- Online Communities and Resources: For those in remote areas or with mobility challenges, online forums and telehealth platforms offer accessible ways to connect with therapists, support groups, and informational resources, breaking down geographic barriers to care.

The concept of trauma-informed communities is gaining traction, where entire systems—schools, workplaces, healthcare settings, and even justice systems—are trained to recognize and respond to trauma in ways that avoid re-traumatization and promote healing. This paradigm shift emphasizes safety, trustworthiness, peer support, collaboration, empowerment, and cultural sensitivity. Ultimately, a strong, understanding, and well-resourced support network can make the difference between mere survival and true thriving for trauma survivors.

Advocacy and Future Directions in Trauma Care in the US

The landscape of trauma care in the United States is continuously evolving, driven by scientific advancements, increased public awareness, and the tireless efforts of advocates. While significant progress has been made, there remains a critical need for continued investment, policy reform, and innovation to ensure that comprehensive, equitable, and effective trauma-informed care is accessible to all who need it. The future of mental health directly hinges on our collective ability to address trauma systematically.

One key area of focus is expanding access to care. This involves not only increasing the number of trained trauma specialists but also integrating mental health services into primary care settings, making it easier for individuals to receive early intervention. Telehealth and digital mental health platforms are playing an increasingly vital role in bridging geographic and financial gaps, democratizing access to specialized therapy and support groups across the nation. Further investment in these technologies is crucial.

Policy reform is another imperative. Advocates are pushing for improved insurance coverage for mental health services, ensuring that trauma therapies are fully covered without excessive out-of-pocket costs. Legislation promoting trauma-informed practices in schools, justice systems, and child welfare agencies is also vital. This systemic approach recognizes that trauma is a public health issue that requires a coordinated, multi-sectoral response, not just individual treatment.

Furthermore, there is a growing emphasis on early intervention and prevention, especially for children. Initiatives like adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) screenings aim to identify children at risk for trauma-related issues early on, allowing for preventative measures and immediate support. Research into neurobiological markers of trauma and personalized treatment approaches continues to advance, promising more targeted and effective interventions in the future. The destigmatization of mental health, particularly trauma, remains a foundational goal. Through ongoing public education campaigns, real-life narratives, and the promotion of resilience, society can continue to shift perceptions, encouraging more individuals to seek help without fear of judgment. The collective commitment to robust research, accessible services, and compassionate communities will define the future of trauma care, ultimately fostering a more resilient and mentally healthy nation.

| Key Aspect | Brief Description |

|---|---|

| 🧠 Neurobiological Impact | Trauma alters brain structures (amygdala, hippocampus, PFC), leading to chronic stress responses. |

| 🏥 Access to Care Barriers | Challenges include cost, stigma, lack of providers, and systemic complexities in the US. |

| ✨ Healing Modalities | Effective therapies include EMDR, CBT, CPT, DBT, and Somatic Experiencing. |

| 🤝 Support Systems | Family, peer groups, and community resources are crucial for sustained recovery. |

Frequently Asked Questions About Trauma and Mental Health

▼

The most common mental health conditions linked to trauma include Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), various anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder, and substance use disorders. Trauma can also lead to complex trauma (cPTSD), which is distinct from traditional PTSD, often resulting from prolonged or repeated exposure to traumatic events, particularly during childhood. It affects emotional regulation, self-perception, and relationships.

▼

Trauma can profoundly alter brain function and structure. It often leads to hyperactivity in the amygdala (the brain’s fear center), reduced activity in the prefrontal cortex (responsible for executive functions), and sometimes even shrinkage of the hippocampus (vital for memory). These changes contribute to symptoms like hypervigilance, difficulty with emotional regulation, fragmented memories, and impaired decision-making often seen in trauma survivors.

▼

Several evidence-based therapies are highly effective for trauma. These include Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT), and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT). Somatic Experiencing (SE) is another key modality that addresses the physiological impact of trauma. The best approach often depends on the individual’s specific needs and the nature of their trauma.

▼

Support systems are crucial for fostering resilience and long-term recovery from trauma. This includes understanding and empathetic family and friends, peer support groups (like those offered by NAMI), and community resources such as crisis hotlines or shelters. These networks provide emotional validation, reduce isolation, offer practical assistance, and help individuals feel safe and connected, supplementing professional therapy.

▼

Common barriers to accessing trauma care in the U.S. include financial constraints due to high costs and inadequate insurance coverage, geographic limitations preventing access to specialized providers, persistent societal stigma surrounding mental health, and a shortage of adequately trained trauma specialists. Additionally, navigating the complex healthcare system can be overwhelming for those already struggling with trauma’s effects.

Conclusion: Paving the Way for a Trauma-Informed Future

Understanding the profound impact of trauma on mental health: finding healing and support in the US is an ongoing, vital endeavor. From the intricate neurobiological changes to the pervasive psychological residues, trauma leaves an undeniable mark on individuals and communities. Yet, the journey toward healing, while challenging, is undeniably achievable. Through evidence-based therapeutic modalities, robust support systems, and a concerted effort towards systemic advocacy and destigmatization, the United States is slowly but surely building a more trauma-informed society. The commitment to compassionate, accessible, and comprehensive care is not just about treating illness; it’s about fostering resilience, restoring hope, and empowering survivors to reclaim their narratives and thrive. The future of mental wellness depends on our collective ability to recognize, respond to, and heal the invisible wounds of trauma with empathy and expertise.